Why Reintroduce a Physical Vacuum?

SERIES I — FOUNDATIONS

The Mechanical Vacuum

Modern physics is extraordinarily successful at predicting what we observe.

It is far less clear about what is actually there.

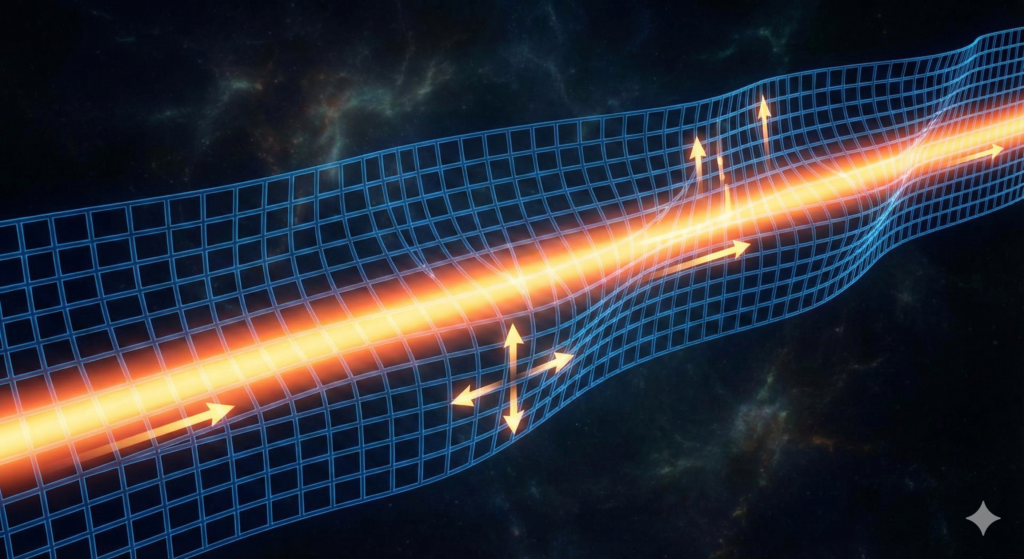

We speak of curved spacetime, fluctuating fields, virtual particles, and probability amplitudes—concepts that work mathematically, yet remain physically opaque. The vacuum, in particular, is treated as both nothing and everything at once: empty of substance, yet capable of carrying energy, momentum, stress, waves, and correlations across the universe.

This blog begins from a simple, unfashionable question:

If something carries stress and supports waves, what is it made of?

The Vacuum as a Stage — and the Cost of Abstraction

In most modern formulations, the vacuum is not a physical object. It is a background:

a geometric manifold in relativity, or a quantum ground state in field theory. This abstraction has advantages—it simplifies calculations and avoids committing to unobservable structure.

But abstraction comes at a cost.

When geometry is treated as fundamental, gravity becomes curvature without mechanism.

When fields are treated as fundamental, forces act without anything being strained.

When probability is treated as fundamental, correlations appear without physical constraint.

The result is a growing collection of anomalies—not numerical errors, but conceptual ones.

This blog takes the position that many of these difficulties arise not from incorrect equations, but from an ontological gap: we have lost track of what the equations are describing.

A Forgotten Question in Physics

Historically, physics did not begin this way.

Researchers such as James Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin routinely asked mechanical questions about space itself. They imagined the vacuum as something that could be strained, twisted, or set into motion—because that was the only known way to explain how waves and forces propagate.

Later developments replaced these mechanical pictures with more abstract formalisms, which worked better mathematically but left physical interpretation behind. Over time, the habit of not asking what is being deformed became normal.

This blog argues that it is time to ask that question again.

What Do We Mean by a “Physical Vacuum”?

By physical vacuum, we do not mean:

- a classical luminiferous aether,

- a rigid crystal lattice filling space,

- or a substance that defines absolute motion.

Instead, we mean something much more modest and testable:

A continuous medium characterized by mechanical properties—such as density, stiffness, stress, and flow—that give rise to the phenomena we describe as fields, forces, and geometry.

This is not an exotic assumption. It is the default assumption in every other branch of physics that deals with waves and forces.

Why Mechanics?

In ordinary materials:

- Waves propagate because the medium resists deformation.

- Forces arise from stress gradients.

- Energy is stored elastically.

- Motion follows from imbalance, not geometry.

If the vacuum supports:

- electromagnetic waves,

- inertial resistance,

- gravitational attraction,

- and global correlations,

then treating it as mechanically inert is the unusual choice—not the conservative one.

The goal of this series is not to discard modern physics, but to reinterpret its successful equations as descriptions of material response, rather than as statements about abstract entities acting without a substrate.

What This Series Will—and Will Not—Do

This blog will:

- reintroduce mechanical intuition into foundational physics,

- define all terminology as it is introduced,

- distinguish clearly between interpretation and formal derivation,

- credit prior researchers where ideas overlap or resonate.

This blog will not:

- claim that existing theories are “wrong,”

- propose superluminal signaling or free energy,

- rely on metaphysics in place of mechanics.

Every claim will be framed in terms of stress, strain, waves, and constraints—concepts that have proven reliable everywhere else in physics.

A Guiding Principle

Before invoking geometry, probability, or fields as primitives, we will ask a simpler question:

What is being deformed, and how does it respond?

The next post begins answering that question by introducing a single mechanical idea—stiffness—and asking what it would mean for the vacuum to possess it.

Next:

→ What Does It Mean for the Vacuum to Have Stiffness?