Matter as a Defect, Not a Thing

SERIES I — FOUNDATIONS

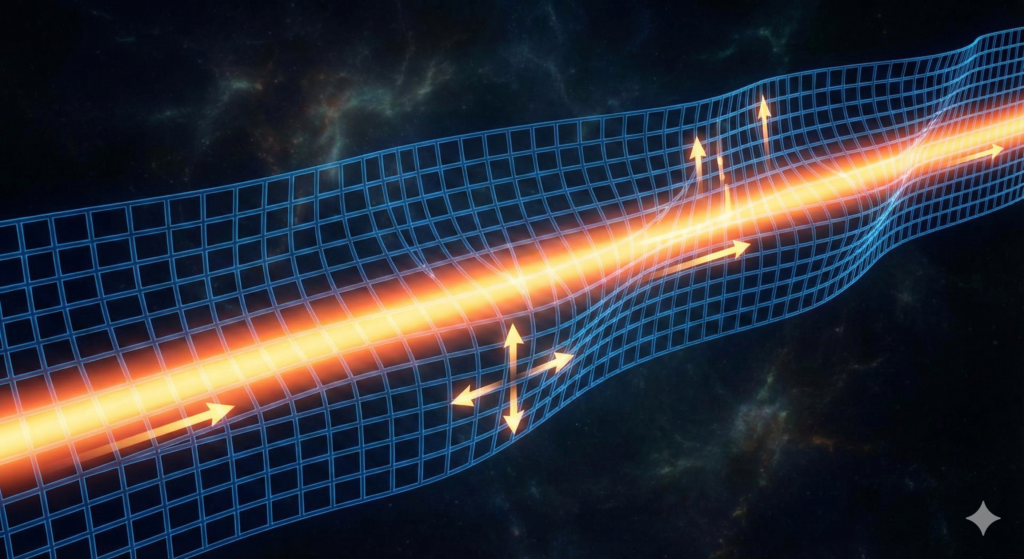

The Mechanical Vacuum

We are accustomed to thinking of matter as stuff: tiny objects moving through empty space. Electrons, atoms, and particles are treated as fundamental entities—things that exist independently of their surroundings.

This post explores a different, mechanically grounded possibility:

What if matter is not something added to the vacuum, but a stable deformation of it?

This idea may feel unfamiliar today, but it arises naturally once the vacuum is treated as a medium capable of supporting stress and waves.

What Is a Defect?

In physics and materials science, a defect is not a flaw. It is a persistent structural configuration of a medium that cannot be removed by smooth deformation.

Examples include:

- a vortex ring in a fluid,

- a knot in a rope,

- a dislocation in a crystal,

- a soliton in a nonlinear waveguide.

In each case, the defect:

- has a well-defined identity,

- can move through the medium,

- carries energy and momentum,

- and persists because of topology, not rigidity.

The medium remains continuous everywhere. Nothing “extra” is inserted.

Vortices as Mechanical Objects

A particularly instructive example is the vortex ring—the familiar smoke ring.

A vortex ring:

- travels as a coherent structure,

- resists dispersion,

- interacts with boundaries and other vortices,

- and behaves like a particle despite being nothing more than organized flow.

Its mass is not intrinsic.

Its inertia arises from the surrounding medium it entrains.

This distinction matters.

Mass Without Substance

In fluid dynamics, an object moving through a medium must accelerate not only itself, but also some portion of the surrounding fluid. This is known as added mass.

A vortex ring experiences inertia for the same reason. Its “mass” reflects how much of the medium must be set into motion to move the structure.

No solid core is required.

If the vacuum behaves as a medium, the same logic applies:

mass need not be a fundamental substance—it can be a measure of displaced or entrained medium.

A Historical Glimpse

This perspective was explored seriously in the 19th century by figures such as Lord Kelvin, who proposed that atoms might be stable vortex structures in an underlying continuum. The mathematical tools of the time were insufficient to make this program predictive, and the idea was eventually abandoned.

What was lost was not the equations, but the question:

how can stable, particle-like behavior emerge from continuous media?

Today, vortex dynamics, soliton theory, and topology provide answers that were unavailable then.

Why Defects Persist

Defects persist because of topological protection.

A vortex cannot simply fade away. To remove it, the medium would have to:

- tear,

- reconnect,

- or undergo a discontinuous transformation.

As long as the medium remains continuous, the defect remains.

This explains why defects:

- have identity,

- conserve certain properties,

- and behave as if they are “objects” even though they are not separate substances.

Rethinking Particles

Seen this way, particles are:

- not points,

- not billiard balls,

- not mathematical abstractions,

but localized, self-sustaining configurations of a medium.

This perspective naturally accounts for:

- inertia as added mass,

- stability without rigidity,

- motion without drag (in a superfluid-like medium),

- and interaction through stress and flow.

It also avoids the infinities that arise when point particles are treated as fundamental.

What This Does—and Does Not—Claim

This post does not claim:

- that matter is literally a smoke ring,

- that particles are classical fluids,

- or that quantum mechanics is being replaced.

It claims something narrower and more conservative:

If the vacuum supports stress and waves, then stable defects are the most natural candidates for what we call matter.

Quantum behavior, charge, spin, and statistics will be addressed later—each as specific modes or constraints acting on these defects.

Setting the Stage

With this final piece, Series I completes its task.

We now have:

- a vacuum that can be strained,

- stiffness that governs waves,

- light as a shear phenomenon,

- and matter as a persistent defect.

In the next series, we apply these ideas to gravity—not to challenge its predictions, but to reinterpret its mechanism.

Next:

→ Gravity Without Geometry