The Periodic Table Is a Standing Wave

SERIES III — ATOMIC STRUCTURE & HARMONICS

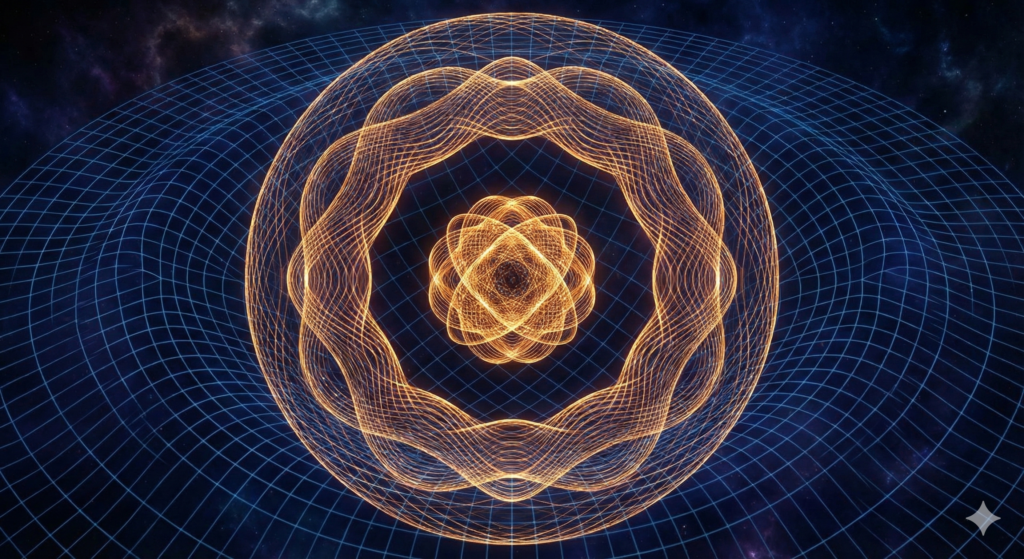

Matter as Standing Wave Geometry

The periodic table is one of the most successful organizational tools in science. It predicts chemical behavior, bonding tendencies, and material properties with remarkable reliability. Yet its deeper structure is usually treated as an accounting scheme rather than a physical phenomenon.

This post asks a different question:

What if the periodic table is not a list of particles, but a spectrum of allowed standing-wave states?

Once matter is treated as a defect in a continuous medium, this possibility becomes difficult to ignore.

Periodicity Is a Physical Clue

Periodic behavior in physics almost always points to resonance.

- Musical notes repeat because strings support standing waves.

- Atomic spectra form series because bound systems admit discrete modes.

- Crystal lattices repeat because of geometric closure.

The periodic table is no exception. Its repeating patterns—rows, columns, shell closures, and chemical families—strongly suggest an underlying wave structure.

The question is not whether waves are involved, but which waves and where they live.

Standing Waves in Plain Terms

A standing wave forms when a wave reflects back on itself and interferes in a stable pattern.

Key features include:

- nodes, where motion is minimized,

- antinodes, where amplitude is maximal,

- discrete allowed modes set by boundary conditions.

Standing waves do not require rigid walls. They arise whenever a system enforces closure conditions—geometric, energetic, or mechanical.

If matter is a localized, persistent excitation of a medium, then standing-wave behavior is not exotic. It is expected.

From Shells to Nodes

In conventional quantum mechanics, atomic structure is described in terms of electron shells and orbitals. This language is operationally useful, but it obscures a simpler mechanical interpretation.

Shell closure corresponds to:

- a state of minimal external coupling,

- a configuration that resists further deformation,

- a node in the system’s response to its surroundings.

Seen this way, shells are not containers for particles. They are stable resonance states of a coupled system: defect plus medium.

Why the Table Repeats

Each period in the table marks the completion of a mode.

When a standing-wave configuration closes:

- the system becomes mechanically inert to small perturbations,

- chemical reactivity drops sharply,

- a new mode must form before interaction resumes.

This is why noble gases appear where they do. They are not special because electrons are “full,” but because the underlying configuration has reached a mechanically closed state.

Columns as Mode Families

Elements in the same column behave similarly because they share:

- the same outer response pattern,

- similar coupling to external stress and flow,

- analogous boundary conditions at the defect–medium interface.

In wave language, they belong to the same harmonic family, differing primarily in scale rather than structure.

This explains why trends repeat across periods despite dramatic changes in size and mass.

A Historical Parallel

Patterns of periodicity and octave-like repetition were noted long ago by thinkers such as Dmitri Mendeleev, who organized elements empirically, and later by Walter Russell, who emphasized wave structure but lacked a mechanical foundation.

This post does not adopt Russell’s conclusions wholesale. It acknowledges his intuition: periodicity is telling us something physical.

With modern continuum mechanics and defect theory, that intuition can be reframed without metaphysics.

What This Perspective Explains Naturally

Viewing the periodic table as a standing-wave spectrum helps explain:

- why elements cluster into families,

- why shell closures are especially stable,

- why atomic size oscillates across periods,

- why certain elements act as structural pivots.

It also prepares the ground for understanding why one element, in particular, occupies an unusually central role.

What This Does—and Does Not—Claim

This post does not claim:

- that electrons are literal vibrating strings,

- that quantum mechanics is being discarded,

- or that chemistry reduces to acoustics.

It does claim:

- that atomic structure reflects resonance and closure,

- that periodicity is a mechanical signature,

- and that wave-based interpretations add physical intuition without altering predictions.

Quantum mechanics remains an effective description.

Standing-wave structure explains why it works.

Looking Ahead

If the periodic table is a spectrum, then:

- some elements correspond to nodes,

- others to maxima,

- and some occupy especially balanced positions.

In the next post, we examine a historical attempt to recognize this structure—and separate insight from speculation.

Next:

→ Walter Russell Was Asking the Right Question