Atomic Shell Closure as a Mechanical Node

SERIES III — ATOMIC STRUCTURE & HARMONICS

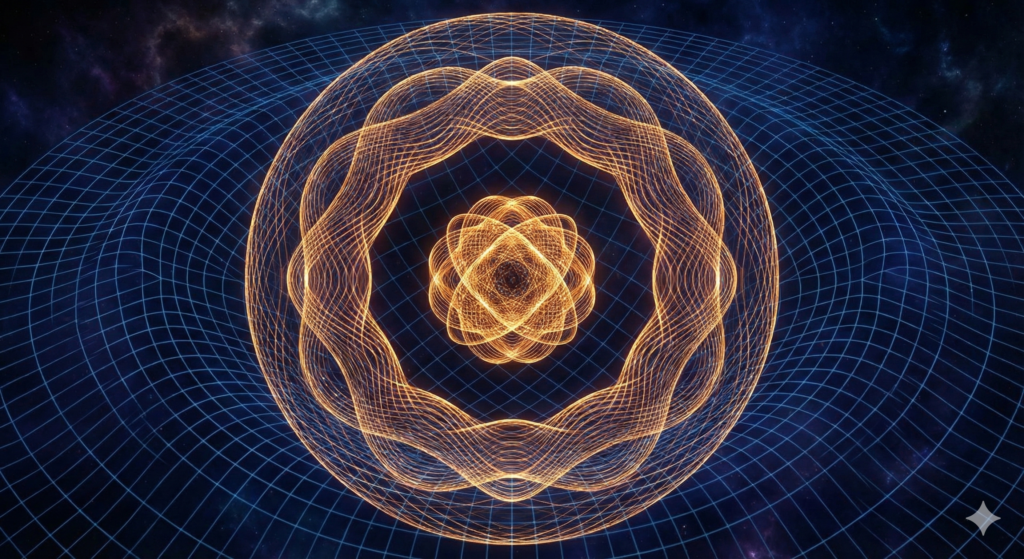

Matter as Standing Wave Geometry

In conventional atomic theory, shell closure is explained by counting electrons. When an orbital is “full,” the atom becomes chemically inert, and a noble gas appears. This accounting works—but it does not explain why full shells are so exceptionally stable, nor why closure produces such a sharp drop in reactivity.

This post reframes shell closure mechanically:

Atomic shell closure corresponds to a node—a state of minimum external coupling—in a standing-wave system.

What Does “Node” Mean Here?

In wave mechanics, a node is a location or configuration where a system’s response to external disturbance is minimized.

- In a vibrating string, nodes barely move.

- In an acoustic cavity, nodes exchange little energy with the surroundings.

- In elastic systems, nodes are mechanically quiet.

Nodes are not empty. They are balanced.

When matter is treated as a persistent defect embedded in a medium, nodes become natural candidates for states of exceptional stability.

From Electron Counting to Coupling

Electron shells are an effective description of atomic behavior, but they focus on internal bookkeeping. A mechanical view asks a different question:

How strongly does this atomic configuration couple to its environment?

Coupling here includes:

- electrical polarizability,

- chemical reactivity,

- susceptibility to deformation,

- and interaction with external fields.

At shell closure, these couplings reach a minimum.

This is not an abstract statement—it is directly observable.

What the Data Already Show

Noble gases exhibit:

- extremely low polarizability,

- minimal chemical bonding,

- high ionization energies,

- and weak response to external fields.

These are precisely the signatures of a node state.

Rather than interpreting these properties as consequences of “filled orbitals,” we can interpret them as indicators that the atomic defect has reached a mechanically closed configuration—one that neither readily absorbs nor transmits stress.

Why Closure Is Sharp, Not Gradual

One of the striking features of the periodic table is how abruptly behavior changes at shell closure. Reactivity does not taper smoothly—it collapses.

Standing-wave systems behave this way.

As a mode approaches closure:

- small changes produce little effect,

- response falls rapidly,

- and once closure is achieved, additional excitation requires forming a new mode.

This explains why the noble gases form such a distinct chemical boundary.

A Mechanical Picture of the Atom

In this framework, an atom is not a nucleus with orbiting particles, but a localized resonance structure maintained by stress and flow in the surrounding medium.

Shell closure occurs when:

- internal oscillatory structure closes on itself,

- boundary conditions are satisfied,

- and net coupling to the external medium is minimized.

The atom becomes mechanically quiet—not because it is “full,” but because it is balanced.

Historical Context

The idea that atoms occupy special stable configurations is not new. Gilbert N. Lewis recognized valence closure empirically, while later quantum theory formalized it mathematically.

What was missing was a mechanical explanation for why closure should coincide with minimal interaction.

The node interpretation supplies that explanation without altering quantum predictions.

Why This Matters Beyond Chemistry

Interpreting shell closure as a mechanical node:

- links atomic stability to wave physics,

- explains why noble gases resist perturbation,

- clarifies why chemical families repeat,

- and prepares the ground for understanding symmetry and centrality in the table.

It also helps distinguish node states from amplitude states—a distinction that becomes crucial in understanding why certain elements behave as structural pivots.

What This Does—and Does Not—Claim

This post does not claim:

- that electrons cease to exist,

- that orbitals are meaningless,

- or that chemistry is being replaced.

It does claim:

- that shell closure reflects minimum coupling,

- that nodes provide physical intuition,

- and that atomic structure can be understood as resonance rather than containment.

Quantum mechanics remains the calculation tool.

Mechanics provides the explanation.

Looking Ahead

If some elements correspond to nodes, others must correspond to maxima—states where coupling, flexibility, and structural possibility are greatest.

One element, in particular, occupies such a position.

Next:

→ Why Carbon Sits at the Center