Why Inertia Exists at All

SERIES VII — LIVING IN A SOLID VACUUM

How Motion, Freedom, and Transparency Are Possible

Up to this point, the picture has been reassuringly quiet.

- Uniform motion produces no drag

- No preferred frame appears

- The medium remains invisible

But there is one situation where the vacuum does respond:

When motion changes.

This response is so familiar that we rarely question it. We give it a name—inertia—and then treat it as fundamental.

In a mechanical vacuum, inertia is not fundamental at all.

It is a material effect.

Inertia Is Resistance to Reconfiguration

When an object accelerates, something very specific happens mechanically:

- The surrounding medium must reorganize

- Stress must redistribute asymmetrically

- Information about the change must propagate outward

None of this can occur instantaneously.

The resistance you experience during acceleration is not a property of the object alone.

It is the cost of reconfiguring the surrounding medium.

Added Mass: A Familiar Mechanical Effect

This phenomenon already exists in ordinary mechanics.

In fluid dynamics, an accelerating object must also accelerate some of the fluid around it. The result is called added mass (or virtual mass).

Key features:

- It appears only during acceleration

- It depends on the displaced volume

- It vanishes for uniform motion

A neutrally buoyant object drifting steadily through water feels nothing.

Push it to accelerate, and resistance immediately appears.

That resistance is inertia.

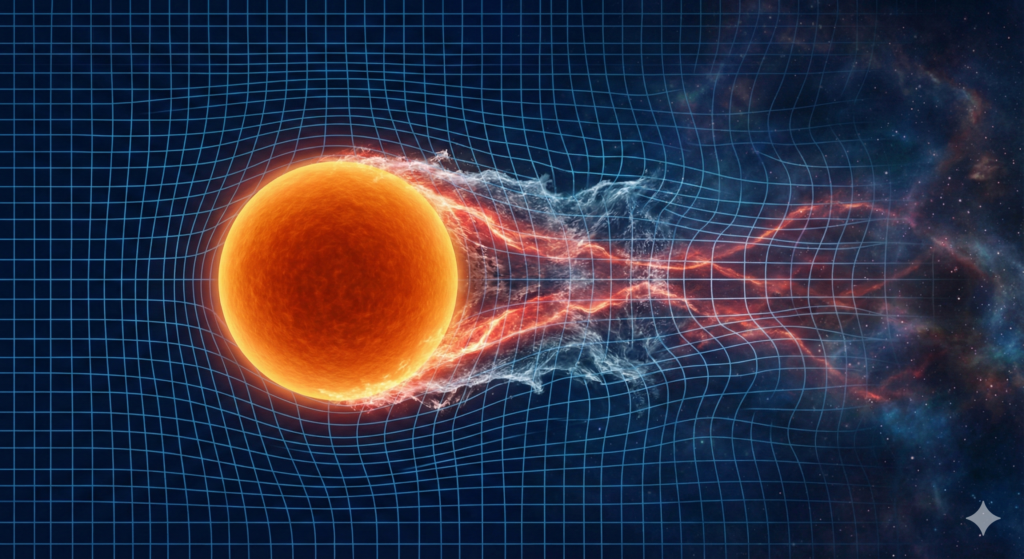

Matter Accelerates the Vacuum With It

In a mechanical-vacuum framework, matter is not an object moving through space. It is a localized defect of the vacuum medium.

When such a defect accelerates:

- The surrounding vacuum must be accelerated as well

- Stress builds ahead of the defect

- Rearward stress relaxes more slowly

The medium resists this imbalance.

That resistance is inertial mass.

Why Inertia Is Universal

This picture explains several deep facts that are otherwise mysterious:

- Why all matter has inertia

Because all matter displaces and entrains the same medium. - Why inertia scales with mass

Because larger defects displace and reorganize more medium. - Why inertia is direction-independent

Because stress reconfiguration costs energy regardless of direction.

No new principle is required.

Inertia follows directly from continuum mechanics.

Why Acceleration Feels Different From Motion

You can feel acceleration because acceleration creates gradients.

Uniform motion:

- No gradients

- No strain

- No sensation

Acceleration:

- Stress gradients

- Delayed redistribution

- Measurable resistance

This is why you feel pressed into a seat when a car accelerates, but feel nothing once it reaches cruising speed.

The medium has pushed back—not against motion, but against change.

A Finite Speed Limit Emerges Naturally

Stress and information in the vacuum propagate at a finite speed—the same speed that governs wave propagation.

As acceleration increases:

- Stress piles up faster than it can redistribute

- Resistance grows nonlinearly

- Further acceleration becomes increasingly costly

A universal speed limit is not imposed geometrically.

It is enforced materially.

This is the same reason objects cannot exceed the speed of sound in air without dramatic effects. The analogy is not poetic—it is mechanical.

Key Takeaway

Inertia is not an intrinsic property of matter.

It is the resistance of a medium to rapid reconfiguration.

Once this is understood:

- Inertia stops being mysterious

- Acceleration becomes physically grounded

- And a deeper unity begins to appear

Because the same mechanism that produces inertia also explains something even more striking:

why gravitational and inertial mass are identical.

That connection is not an assumption.

It is a consequence—and we’re now ready to approach it.