Light as a Shear Wave

SERIES I — FOUNDATIONS

The Mechanical Vacuum

Light is one of the most familiar phenomena in physics—and one of the most conceptually neglected.

We learn early that light is a wave, and later that it is a transverse wave. We calculate its frequency, wavelength, polarization, and speed with extraordinary precision. Yet we rarely pause to ask a basic mechanical question:

What kind of thing supports a transverse wave?

This post explores that question carefully and shows why answering it forces us to reconsider what the vacuum must be capable of doing.

What Does “Transverse” Actually Mean?

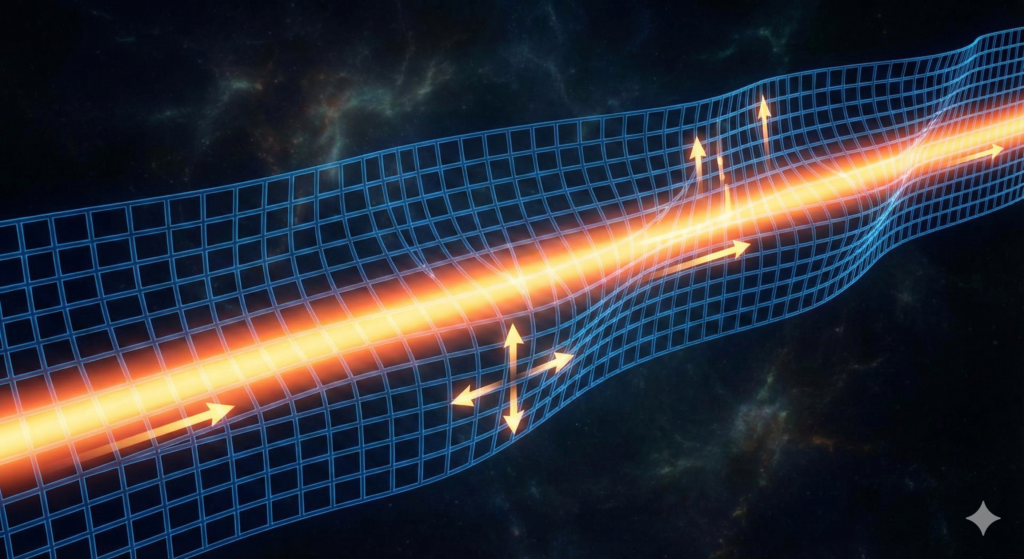

A transverse wave is one in which the motion of the disturbance is perpendicular to the direction of propagation.

- On a rope, the rope moves up and down while the wave travels sideways.

- In a solid, particles slide sideways as the wave passes through.

- In light, the electric and magnetic oscillations are perpendicular to the direction of travel.

This is not a superficial detail. It is a mechanical classification.

Transverse motion requires resistance to sideways deformation—what we previously defined as shear stiffness.

A Hard Mechanical Fact

In continuum mechanics, there is a strict rule:

A medium without shear stiffness cannot support transverse waves.

Fluids illustrate this clearly. Liquids and gases support pressure waves (sound), but not transverse shear waves. If you try to send a sideways disturbance through water, it immediately relaxes—it cannot sustain shear stress.

Solids, by contrast, support both longitudinal and transverse waves precisely because they resist changes in shape.

This rule applies universally. It is not optional. It is not philosophical.

Light’s Uncomfortable Implication

Light is experimentally confirmed to be transverse:

- its polarization can be rotated,

- its oscillations have direction,

- its behavior matches transverse wave equations exactly.

And yet, the vacuum is usually described as having no mechanical properties at all.

This creates a quiet contradiction.

Modern physics resolves it by abandoning mechanical language altogether, describing light as an excitation of an abstract electromagnetic field that does not require a medium. Mathematically, this works perfectly. Mechanically, it explains nothing.

This blog takes a different approach: instead of asking how to avoid a medium, we ask what kind of medium would be required.

Maxwell’s Original Insight

This question is not new.

James Clerk Maxwell explicitly described electromagnetic waves using mechanical analogies. His equations emerged from attempts to understand stresses and rotations in an underlying continuum. While the mechanical models of his era were incomplete, the intuition was sound: waves imply something that is being strained.

Later generations kept Maxwell’s equations and discarded the substrate. The success of the equations made the loss easy to overlook.

But equations do not eliminate mechanics—they only hide it.

Polarization as a Mechanical Clue

Polarization provides a particularly strong hint.

A wave can only be polarized if:

- it has a preferred direction of oscillation,

- that direction is physically meaningful,

- the medium distinguishes between sideways orientations.

Polarization is trivial in solids and impossible in fluids without structure.

That light is polarizable tells us that whatever carries it must respond anisotropically to shear—even if that response is extremely subtle.

Shear Waves Without a Solid Lattice

At this point, a clarification is essential.

Calling light a shear wave does not mean:

- the vacuum is a rigid solid,

- space resists motion,

- objects scrape against a background medium.

Shear stiffness can exist without friction, drag, or dissipation. Superfluids and elastic continua support shear responses while remaining extraordinarily transparent to motion.

What matters is not rigidity, but resistance to deformation.

The Wave-Speed Connection (Revisited)

Recall from the previous post that transverse wave speed in any elastic medium is set by:

wave speed ∝ √(shear stiffness / density)

We are not yet applying this to light numerically. We are establishing a logical dependency:

If light is transverse,

and transverse waves require shear stiffness,

then light’s speed must reflect a ratio of mechanical properties.

This conclusion follows before invoking relativity, quantum theory, or geometry.

Why This Perspective Matters

Once light is understood as a shear phenomenon:

- wave speed becomes a material property,

- polarization becomes a mechanical response,

- refraction becomes a constitutive effect,

- geometry becomes descriptive, not causal.

None of this contradicts established electromagnetic theory. It simply asks what that theory is describing.

Looking Ahead

In the next post, we take the next logical step.

If the vacuum supports shear waves and resists deformation, then localized, persistent disturbances in that medium should be possible. These disturbances will not behave like ordinary objects—they will behave like defects.

That is where matter enters the picture.

Next:

→ Matter as a Defect, Not a Thing