What Does It Mean for the Vacuum to Have Stiffness?

SERIES I — FOUNDATIONS

The Mechanical Vacuum

In everyday language, stiffness sounds like a property of solid objects: steel beams, rubber bands, springs. It feels out of place when applied to empty space. And yet, stiffness is one of the most fundamental quantities in physics—because it governs how forces propagate and how waves travel.

If the vacuum supports waves, resists acceleration, and stores energy, then stiffness is not an optional idea. It is unavoidable.

This post introduces stiffness carefully, defines what it means mechanically, and explains why the concept matters long before we apply it to gravity, light, or atoms.

Stiffness in Plain Terms

At its core, stiffness answers a simple question:

How hard is it to deform something?

More precisely, stiffness measures how much restoring force appears when a system is displaced from equilibrium. Pull on a spring, bend a ruler, compress a gas—each responds differently, because each has different stiffness.

In physics, stiffness is not a vague quality. It is a measurable parameter that links:

- force to deformation,

- stress to strain,

- wave speed to material properties.

Not One Stiffness, but Several

In a continuous medium, stiffness comes in different forms. The two most important are:

Bulk stiffness (bulk modulus)

- Resistance to compression or expansion

- Governs longitudinal, pressure-like responses

Shear stiffness (shear modulus)

- Resistance to shape change at constant volume

- Governs transverse, sideways motion

These are not abstract distinctions. They determine what kinds of waves a medium can support.

A fluid has bulk stiffness but essentially no shear stiffness.

A solid has both.

This distinction will matter enormously later.

Why Shear Stiffness Is Special

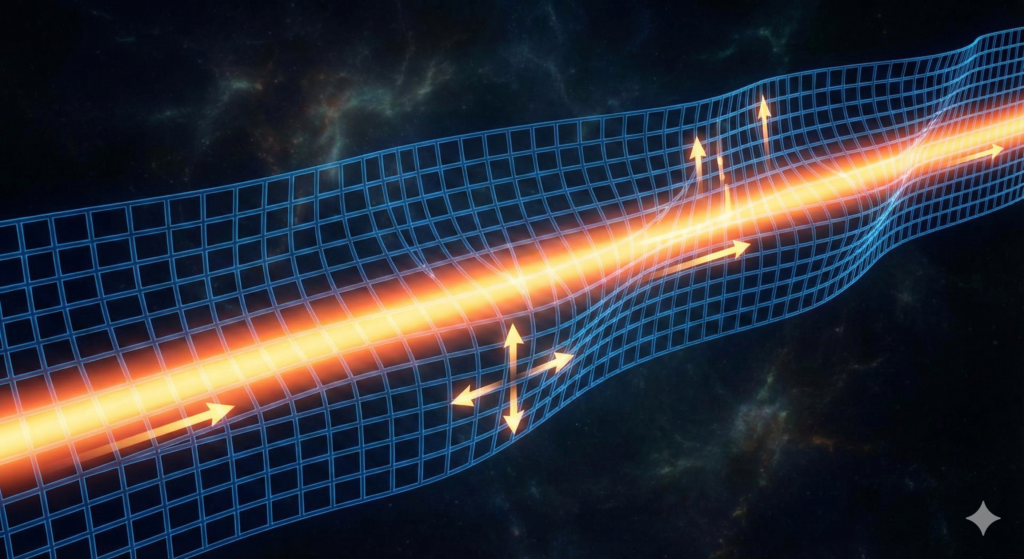

Shear stiffness controls transverse waves—waves where the motion is perpendicular to the direction of travel. Guitar strings, seismic S-waves, and elastic vibrations in solids all rely on shear resistance.

This leads to a crucial mechanical fact:

No shear stiffness, no transverse waves.

That statement is not philosophical. It is experimental.

When we later note that light is a transverse wave, this fact will become difficult to ignore.

The Wave-Speed Connection

In any elastic medium, wave speed is not arbitrary. It is set by a ratio of material properties.

For transverse waves, the relationship is:

Wave speed ∝ √(stiffness / density)

This is true for steel, rubber, rock, and any other elastic material. There is nothing exotic about it. Stiffer materials transmit disturbances faster; denser materials respond more sluggishly.

At this stage, we are not applying this formula to the vacuum. We are simply establishing a rule that applies whenever transverse waves exist.

Stress, Strain, and Stored Energy

Stiffness is also how materials store energy.

When a medium is deformed:

- strain describes how much it is deformed,

- stress describes the internal forces resisting that deformation,

- elastic energy is stored in the process.

This energy is real, local, and mechanical. It does not require particles colliding or forces acting at a distance. It resides in the configuration of the medium itself.

If the vacuum participates in energy storage—as modern physics insists it does—then stiffness is the natural bookkeeping variable.

A Brief Historical Note

Early thinkers such as Augustin-Louis Cauchy and George Green developed elasticity theory precisely to formalize how stresses and strains propagate through continuous media. Their work underlies modern continuum mechanics, seismology, and materials science.

When modern physics abandoned mechanical language for fields and geometry, it did not invalidate this framework—it simply stopped applying it to the vacuum.

This blog asks whether that omission was justified.

What We Are—and Are Not—Claiming

At this point, we are not claiming that:

- the vacuum is a solid like steel,

- space is filled with a literal lattice,

- stiffness implies rigidity or resistance to motion.

We are claiming something much narrower:

If the vacuum supports transverse waves and stores elastic energy, then describing it as having effective stiffness is the most conservative possible assumption.

This is a matter of consistency, not speculation.

Why This Matters Going Forward

Once stiffness is admitted as a legitimate property of the vacuum:

- wave speed becomes a material parameter,

- forces become stress gradients,

- geometry becomes a description of deformation, not a cause.

Everything that follows—light, gravity, inertia—will build on this single mechanical idea.

But first, we must confront the most familiar wave of all.

Next:

→ Light as a Shear Wave