Why Carbon Sits at the Center

SERIES III — ATOMIC STRUCTURE & HARMONICS

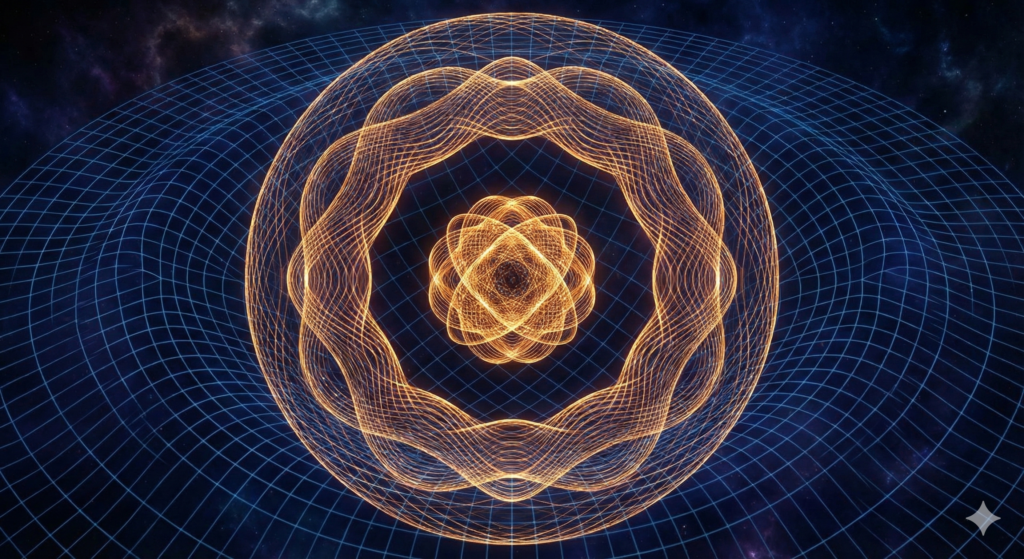

Matter as Standing Wave Geometry

Carbon’s role in chemistry is so familiar that it is rarely questioned. It forms chains, rings, sheets, and frameworks. It bonds flexibly yet stably. It supports complexity without collapsing into rigidity or chaos.

This is usually presented as a fortunate coincidence of electron configuration.

This post argues something stronger:

Carbon occupies a mechanical maximum—a balanced antinode—within the standing-wave structure of the periodic table.

Life does not arise because carbon is lucky.

It arises because carbon sits at a structurally privileged position.

Nodes and Antinodes Revisited

In the previous post, we described shell closure as a node: a configuration of minimal coupling to the surrounding medium. Noble gases are mechanically quiet. They resist interaction.

But standing-wave systems also have the opposite feature:

- antinodes, where response is maximal,

- where deformation is easy but controlled,

- where coupling is strong without being unstable.

Nodes are inert.

Antinodes are generative.

If the periodic table reflects standing-wave structure, we should expect certain elements to occupy antinodal positions.

Carbon does exactly that.

Carbon’s Unusual Balance

Carbon exhibits a combination of properties that rarely coexist:

- strong covalent bonding,

- multiple stable bonding geometries,

- moderate electronegativity,

- high structural flexibility,

- and resistance to runaway reactions.

Mechanically, this describes a configuration that:

- couples efficiently to its environment,

- redistributes stress without fracture,

- and supports rearrangement without loss of identity.

That is the definition of an antinode in a constrained system.

Why Group 14 Is Special

Carbon sits in Group 14, midway between:

- elements that readily donate electrons,

- and elements that readily accept them.

Electronically, this is described as “four valence electrons.”

Mechanically, it means something more subtle:

Carbon neither locks itself closed nor destabilizes under coupling—it transmits structure.

This makes it uniquely capable of forming extended networks that are:

- stable,

- adaptable,

- and information-bearing.

Silicon shares some of this behavior, but its larger scale shifts it away from the optimal balance. Other elements fall too far toward rigidity or reactivity.

Structure Without Brittleness

In materials science, systems that support complexity must satisfy a narrow condition:

- too stiff, and they fracture,

- too soft, and they collapse.

Carbon sits near this mechanical sweet spot.

Its bonds are strong enough to persist, but flexible enough to rearrange. This allows:

- long chains,

- branching structures,

- folded geometries,

- and reversible transformations.

From a standing-wave perspective, carbon resides near a maximum in usable amplitude, not at an extreme.

A Standing-Wave Interpretation

Within the mechanical medium framework:

- noble gases correspond to nodes (minimum coupling),

- highly reactive elements lie near unstable regions,

- carbon corresponds to a stable antinode.

This explains why:

- chemistry “turns on” dramatically at carbon,

- complexity accelerates rather than tapers,

- and structural diversity explodes rather than saturates.

The periodic table is not merely repeating—it is modulating.

Historical Perspective

Chemists such as Friedrich Wöhler and Gilbert N. Lewis recognized carbon’s uniqueness empirically. Later quantum theory explained how carbon bonds, but not why this balance exists.

A mechanical standing-wave view addresses the “why” without altering the successful calculations.

What This Does—and Does Not—Claim

This post does not claim:

- that life could only exist with carbon,

- that chemistry is reducible to acoustics,

- or that electron theory is wrong.

It does claim:

- that carbon’s centrality reflects mechanical balance,

- that its versatility is structural, not accidental,

- and that the periodic table encodes more than bookkeeping.

Carbon is not special because it sits in the middle of a chart.

It is special because it sits at a resonant center of response.

Closing Series III

With this post, the standing-wave interpretation of atomic structure is complete.

We have seen that:

- periodicity reflects resonance,

- shell closure reflects nodes,

- and carbon reflects an antinode of structural possibility.

In the next series, we return to fields and forces—and show that electromagnetism, too, can be understood as stress and flow within the same medium.

Next:

→ Electromagnetism as Stress–Flow, Not Force